"

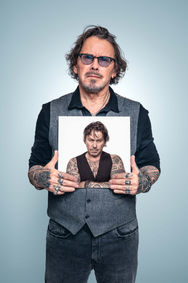

THIS IS PARKINSON´S

TEN YEARS LATER

"

2014

My family lives with the disease too—and probably feels even more strongly than I do that it’s beyond their control.

The medications changed my behavior in ways that were hard for them. But things got much better after I had DBS surgery. An implanted stimulator now delivers electrical impulses to my brain.

Challenges usually bring some opportunities too, and for me, it’s important to look for them.

Geir Paulsen

Share this story

"

2024

“What do you think when you see that old photo of yourself?”

“What I feared most was for my marriage. The meds had changed my personality in a really bad way. I won’t say more than that—that’s enough. But it turned out the way I feared.”

Geir Paulsen (55) sits at the kitchen table in his Oslo apartment. Well, “sits” is a stretch. I’ve rarely met anyone so dyskinetic. Arms and legs flail, his head swings side to side, his torso rocks back and forth.

His wiry body jerks constantly, making it hard for him to do the things he wants. It’s tough to watch. When he’s out, people stare—and I know it bothers him. Soon, he’ll be “off,” and then it’s the opposite: he can barely move.

“Luckily, I have a a personal assistant 42 hours a week. Highly recommended! And home nurses drop by for short visits.”

He’s struggled with dyskinesia for a long time. He thinks it started back in 2007 when he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s. At that time he was prescribed large doses of levodopa, which he suspects played a role.

“In the beginning, I was like a Duracell bunny—running from mountaintop to mountaintop.”

The so-called “therapeutic window” was already closing for Geir. Too little medication gave little benefit, but if he added a bit more it would make him hyperkinetic. It was near impossible to find the right balance. On top of that, his impulse control worsened—not because of the disease itself, but probably as a side effect of the meds.

When I photographed him ten years ago, he had just had DBS surgery. A few years later, he also got a Duodopa pump, which delivers a steady flow of medication. The device hangs on his stomach and pumps 3 ml of Levodopa per hour directly into his small intestine.

“It works really well for me. Vitamins and supplements help too. I’ve changed my diet—that’s super important.”

Geir eagerly talks about the latest Parkinson’s research, but it’s hard to understand him. He has so much knowledge he wants to share, but his speech is impaired, so our conversation takes time.

He tells me he went on disability pay in 2019. The following year, he was in a store when someone suspected he was drunk. When he got into his car to drive home, the police pulled him over with lights flashing. With slurred speech, he tried to explain that it wasn’t alcohol—it was Parkinson’s. After that, he lost his driver’s license.

Later came the breakup with his wife.

“Ten years ago, I thought I’d beat this. I told my kids I’d be much better after ten years. But at that point, things looked bad.”

Geir now lives alone in an apartment in Skøyen, Oslo—not exactly tidy. A spinning bike stands in the middle of the living room. Pills are scattered on the table. A few lampshades are missing. On the kitchen counter, a machine from the home nurses spits out Sinemet eight times a day. He wishes he could move back in with his ex-wife and their two kids.

“It’s lonely and boring. I miss having a girlfriend.”

I’ve known Geir for ten years now. He’s an energetic, curious, social, and cheerful guy who’s become seriously ill and is trying to make the best of it. He prefers to talk about what makes him optimistic: research.

“I read about a supplement study at Haukeland Hospital. Then I went to the health store and stocked up. I think I had something like early dementia, so I looked up those substances and suddenly felt much sharper. It’s called Duranoct and contains various natural compounds. And I’ve also started taking Nicotinamide Riboside—1,000 mg daily. It works.”

Always the optimist—that’s Geir. Every time I meet him, he says he feels better. But does he really? Or is it a coping strategy?

“I like talking about hope because then people stop and listen. I can stand there and chat for an hour.”

But the past year has been tough. The breakthrough he’s been waiting for should be here by now. He’s increased his supplements but isn’t training as much.

“I’m running out of tricks, but I can’t give up. The things we used to do to fight Parkinson’s are even more important now, ten years later.”

“Do you believe in a cure within ten years?”

“Yes, I do. In two to seven years, I think someone will come out and say they’ve been cured. I don’t think Parkinson’s is one disease—I think it’s several. You and I don’t have the same illness—I’m pretty sure of that.”

I press him: “But if Parkinson’s isn’t one disease, how can they find a cure?”

“Exactly because there are different types—it’ll be easier to cure some of them, not all.”

“How’s your quality of life?”

“My quality of life now depends on how much time I get with my kids. That means everything to me. The best thing I know is coaching them and helping them build a good life.”