"

THIS IS PARKINSON´S

TEN YEARS LATER

"

2014

“I work seven days a week. I don’t want to be defined by Parkinson’s. I’m Bård—not that guy with Parkinson’s. The disease has awakened something in me, and that courage makes me strong. But I know it’s there and that in the end it will win. Right now, though, I am winning—and it feels amazing.”

Bård

Share this story

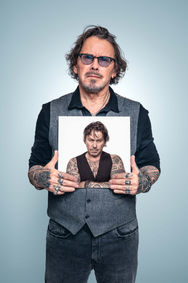

In the photo: Bård with his wife Karine

"

2024

“The story you’re about to tell me—are you sure you want to share it?”

“Yes we are. We’ve thought a lot about the kids, but we want people to understand how serious this is. So even though it costs us something, we’ve decided to tell our story.”

Bård Moshagen (55) was a busy IT guy—43 years old, with a house under construction and the chaos of small children—when he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s in 2012. He started on Parkinson’s medication. Two years later, I photographed him.

“I thought you looked SO handsome,” says his wife, Karine, as she reads his defiant words from back then. “You had just had the diagnosis, and you handled it so well!”

“What I hear is a man who wasn’t himself,” Bård replies.

The year Bård was diagnosed, new treatment guidelines had just come out in Norway. Dopamine agonists were now to be recommended over levodopa as the first-line treatment for younger people with Parkinson`s Disease. Bård was prescribed Sifrol, a dopamine agonist.

Soon, strange things started to happen.

“It started with restlessness at work. I got into conflict with my boss. So I started my own company, brought my wife on board, invested our savings, and took out a loan on the house.”

Bård launched a company specializing in IT solutions for document management and digitalization—and it started growing fast.

Before long, he had businesses in the U.S., Spain, Denmark and Norway.

“At this point I was already on my way to becoming a different man, and the business world was the perfect arena. When you’re traveling, no one’s keeping tabs on you, right? By the time you photographed me I was deep into the personality changes.”

Parkinson’s medications are meant to compensate for the brain’s lack of dopamine—a key neurotransmitter. But dopamine isn’t just about motor control; it’s about survival. When we eat, whan we have sex, when we care for our children or seek new experiences, these are all experiences that release dopamine in the brain, rewarding us and motivating us to repeat those behaviors.

But for many the meds turn out to be too much of a good thing. Bård becomes hypersexual. In the winter of 2014, he’s away on a five-week stay at an institution to learn about exercise for people with Parkinson’s. Hardly a day goes by without him having sex while he’s there.

“It was more like a sexcamp than a training camp,” he says.

The dopamine agonists give Bård lots of energy which he pours into his businesses. He gets friends and family to invest in the venture. Through his companies he’s able to borrow money, and that money is easily spent.

“I was high on work. Then in the evenings I would get high on other things and then I started seeing prostitutes.”

“Let me make a wild guess: Your neurologist didn’t know anything about this.”

“No. In the summer of 2015, a year after your project, my wife caught on. She could see that something was wrong, she read about the side effects of Sifrol, and it was like reading about her own husband. So she contacted the doctor. Later, one of my psychologists told me that Sifrol works in the same way as small doses of cocaine.”

Bård had developed ICD—Impulse Control Disorder.

“I couldn’t control my behavior anymore. I had racked up huge debts, and then they started tapering me off the medication.”

“What did the neurologist say?”

“He had never seen a case this bad. I didn’t have to say much—Karine ran the show.”

At this point Bård is starting to actually believe that everything is going to be allright. But giving up the dopamine and the euphoria is hard.

“When I had finished the tapering off and could demonstrate that I had done what I was expected to, everyone relaxed, and so I started again. Nobody had taken away the leftover meds. I had a shopping bag full of them.”

That bag would last a year and a half.

“This is very painful for me,” Karine admits. “The neurologist told me to return the meds to the pharmacy but then I thought perhaps Bård needed them for tapering. Looking back, I think all of this could have been avoided. But of course, he could always have found a way to trick me.”

By autumn of 2015, Bård was taking almost the maximum dose of the dopamine agonist Sifrol. The expensive lifestyle continued—in secret. Bård was convinced the companies would succeed and the loans would pay themselves off.

“In the first four years I splashed out between four and five million Norwegian kroner annually. The loan market was wide open. A lot went on travel—I loved flying business class. There were luxury hotel suites at 4,000 kroner a night, expensive dinners, and an extravagant lifestyle.”

“How much could you spend in one night?”

“The worst case was about 165,000 kroner.”

“And this went on for years?”

«Yes. At one luxury hotel in Amsterdam as I walked through the entrance door several prostitutes cheered me from the bar – Hello Bård! Great to see you again!»

“It wasn’t just in Amsterdam?”

“No, it was in Estonia, Prague, Hungary, Portugal, Spain, Denmark—everywhere I traveled.”

By fall 2017, the financial situation was getting tight, and Bård was becoming increasingly mentally unstable. He convinced his GP to prescribe more Sifrol. Now the neurologist reacted—but Bård had already picked up a 100-pack.

“The GP was furious, the neurologist was furious—everyone was yelling at me. But I was happy.”

“Like narcotics.”

“Yes.”

“Are we getting close to a turning point now?”

“At the turn of the year 2017–2018, several serious things happened. One weekend as I saw my parents in their home town I visited a prostitute.”

When Bård gets home, he discovers that 8,000 kroner has been stolen from him. He goes back to the apartment he’d been in and pounds on the door.

“The door opens, and out comes this huge guy—two meters tall—with a machete in his hand. He headbutts me, drags me into the hallway, and asks what the hell I’m doing. I have to defend myself against the machete and end up with a cut on my hand, while this guy is standing there with a wild look in his eyes.”

The man says he’s killed people like Bård for a lot less money and threatens to go after his family if Bård goes to the police. But Bård is allowed to leave—and he goes straight to the police, who launch a major armed operation. It turns out this is a married couple running a scam, but no one had dared report them before.

“The day after the machete incident, I had a long talk with a young police officer who looked me straight in the eye and said I had to stop this nonsense. ‘You’re destroying your life if you keep this up,’ she said.”

Bård’s parents are beginning to realize the money they’ve poured in is gone. Still, they stand by him. At this point Bård’s mother suffers a serious cancer relapse and he receives a summons to Bergen District Court. The tax authorities are ready to declare him bankrupt for unpaid taxes. His accounts are as mess. It’s chaos.

“I decided that while my mother was still alive I would have to get in control of my life. That was a turning point. I quit Sifrol, and in March 2018, she passed away. I held myself together until after the funeral. Then I sank into a depression that, at its worst, lasted a year and a half.”

“By then, your companies were bankrupt?”

“The companies had gone under, and everything I had done came to light. I started to become myself again and understood the consequences of what I’d done. I had lied and deceived everyone around me, and the people closest to me were the ones who suffered the most. They were left with personal debt and nothing in return. That’s still hard for me to talk about. Karine almost left me several times.”

“I was devastated,” she says. “A lot of people thought I should leave. But it wasn’t that simple—he had put me in massive debt, and what would I be leaving to? I couldn’t handle everything that was happening; it was way beyond my control. I had the kids to take care of. Going to work was hard, but it was also a refuge where I could think about something other than debt and a mentally unstable husband.”

Meanwhile, the debt collection notices start pouring in, and none of the banks will cooperate. Now Bård summons what strength he has left and starts working on a settlement with his creditors. The key criterion for getting a public debt settlement is that you owe so much it’s unlikely you’ll ever pay it back in your lifetime.

“At this point, were you unemployed?”

“No, from the autumn of 2017 I was on 100% sick leave—and I had over 20 million kroner in debt.”

Five million was the loan that they had on their house. But what about the remaining fifteen million? There were many creditors. To qualify for a public debt settlement, there are certain requirements.

“Did you actually stand a chance of winning this process?”

“I got help from a family member who’s a lawyer. The case went through mediation, forced settlement, Bergen District Court, and then the Gulating Court of Appeal. And there, in the appeal, the moral aspect was the challenge. It ended with one judge against and two in favor. I won by the smallest possible margin.”

Bård was granted a public debt settlement.

“Why are you telling this story?”

“People need to understand how dangerous Parkinson’s medications can be. We’re concerned that these drugs are still prescribed without thorough screening. I was evaluated for DBS (Deep Brain Stimulation surgery) at the National Hospital, and one of the steps was a psychosomatic test.”

Together with a psychiatrist, Bård had to go through a 400-page question form and then had a follow-up conversation.

“That’s when I learned that DBS can also affect impulse control—and I scored 5 out of 5 on risk.”

“So that’s where the questions you’ve been asking for finally came up?”

“Exactly! There actually is a method to assess the risk of impulse control disorders—but it’s only used for DBS evaluations, not when prescribing pills.”

“So no DBS for you.”

“No DBS for me.”

Today, ten years after we first met, it is difficult to see that Bård has Parkinson’s Disease. What’s more noticeable is his vision problem—a condition called Stargardt Disease.

“How is your Parkinson’s?”

“Tolerable,” Bård answers briefly.

Karine adds:

“We’ve had so much financial trouble that Parkinson’s has taken the back seat, but in the past six months, I’ve noticed it creeping back into our lives.”

“I still feel lucky,” Bård concludes, “because the disease has progressed slowly. I’m doing pretty well. I work out every day, the family is doing fine, and friends have actually started coming back.”